Balancing Export Controls on AI and Innovation

How do U.S. policymakers maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of technologies with both commercial and military applications?

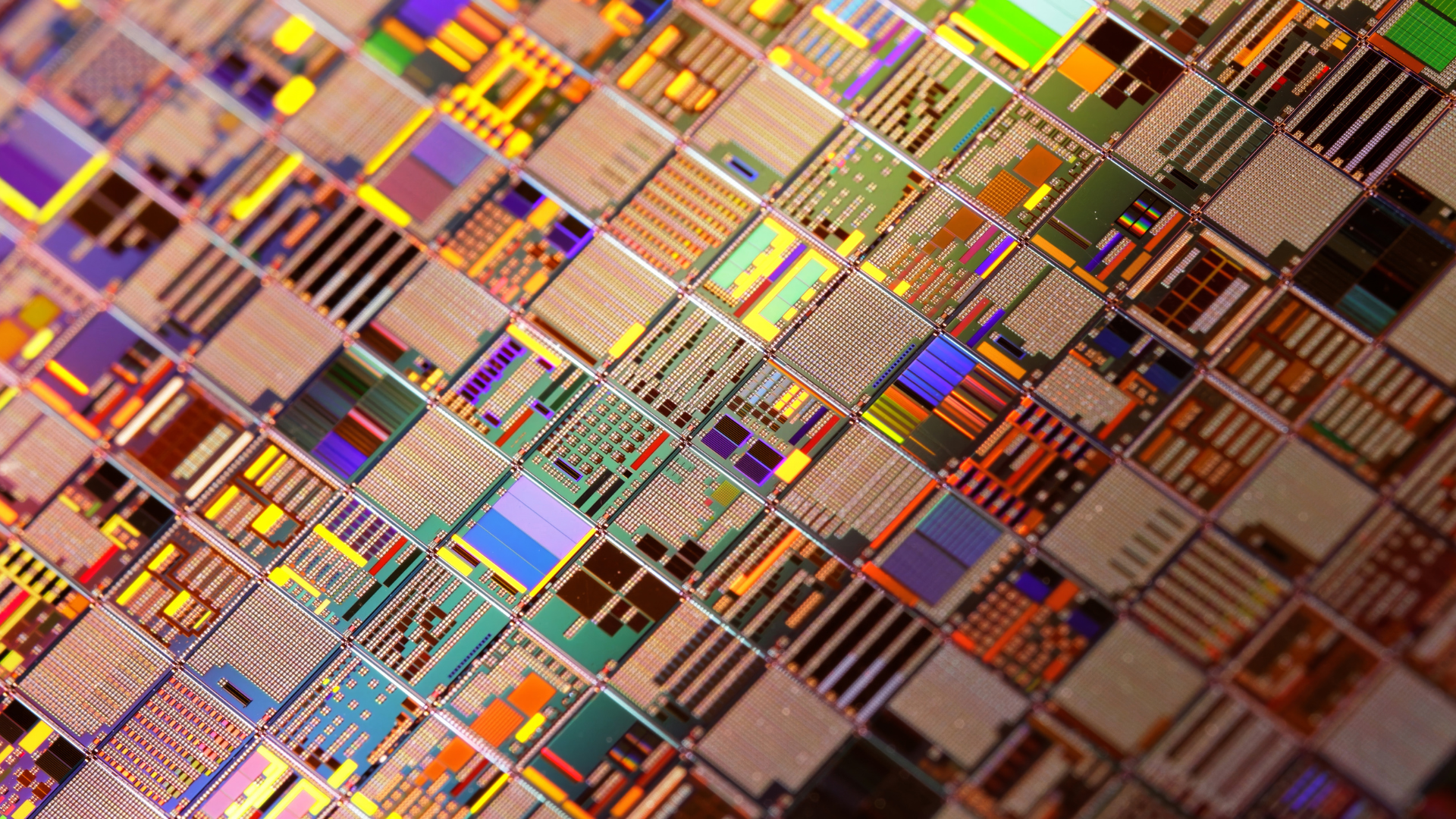

This longstanding conundrum takes on even greater significance with advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI), a truly transformative technology. In retaliation for the United States' chip bans, China recently imposed export controls on rare earth elements, lithium batteries, and graphite—critical for semiconductors and AI hardware, threatening global supply chains and intensifying U.S.-China rivalry.

Innovations in AI will have a disruptive effect on technology, affecting every aspect of our lives. Perhaps most importantly, it will impact national security in areas that include threat detection, cyber defense, and strategic decision-making. Accessing vast data sets of all source intelligence and machine learning will enable nations to better predict adversary actions from terrorist plots to cyber-attacks. AI will make the expanded use of autonomous drones in military operations possible and facilitate the optimization of supply chain operations. Consequently, global leaders in the development of AI will have a strategic advantage in an asymmetric world.

The U.S.’s current policy emphasizes leading international AI diplomacy and security by leveraging U.S. dominance in data centers, computing hardware, and AI models to build an enduring global alliance, while preventing adversaries from benefiting from American innovations. To achieve this, the U.S. must export its comprehensive AI technology stack—including hardware, models, software, applications, and standards—to allies and partners willing to join the alliance, meeting global demand and reducing dependence on rival technologies. At the same time, the policy calls for the United States to deny adversaries access to advanced computing resources critical for economic and military advantages.

In an apparent conflict with this policy, two leading AI chip producers, Nvidia and AMD, recently reached a controversial deal with the current administration. These firms will be allowed to export lower-performance chips (M1308 and H20) to China but will pay the U.S. government 15% of the revenue.

Will this action increase America’s competitiveness in AI technology without accelerating China’s military ambitions? As U.S.-China tensions rise, including China's recent rare earth curbs, striking the right balance is critical to promote global innovation and, at the same time, not accelerate China’s advancements. Comprehensive restrictions threaten to undermine domestic and allied innovation. Consequently, a nuanced, targeted approach—combining smart enforcement, international alliances, and incentives for ethical AI development—is key to leading the global race without self-sabotage.

Evolution of U.S. AI Export Controls

Export controls on AI are contained in the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). They restrict exporting dual-use technologies like advanced semiconductors, AI software, and hardware that could enable civilian breakthroughs and military applications. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) is charged with enforcing export controls, specifically targeting items with potential for weapons development or human rights abuses.

The United States started imposing bans on high-performance chips during the 2018 U.S.-China trade war. Under Biden, the January 2025 AI Diffusion Rule expanded controls to prevent indirect proliferation, mandating licenses for AI training hardware even in third countries. However, the Trump administration rescinded this rule on May 13, 2025—just two days before its compliance deadlines kicked in—opting for a more "targeted" strategy focused on end-users rather than blanket prohibitions. This shift closed loopholes for foreign-owned semiconductor fabs in China while emphasizing case-by-case reviews and ramped-up due diligence, including end-user verification and restrictions on Middle East data centers tied to China.

China has aggressively countered the latest restrictions, stockpiling Nvidia GPUs before the bans tightened and turning to smuggling networks via Malaysia, Singapore, and the UAE. The U.S. authorities charged two Chinese nationals in California with smuggling $100 million worth of Nvidia AI chips to China in August 2025, highlighting the difficulty of enforcing the export controls. Another recent report revealed Chinese firms' stockpiling and smuggling of banned GPUs. It also highlighted Huawei's role in fabricating restricted chips via TSMC, while DeepSeek[1] also evaded controls to aid military projects.

Globally, allies like Japan and the Netherlands have aligned with U.S. controls, updating their regimes in early 2025 to restrict semiconductor tools (essential to high-end chip making and a choke point in the supply chain), with the Wassenaar Arrangement[2] updates in September 2025 aligning EU lists on dual-use AI technology. This coordinated international effort underscores the high stakes in maintaining technological dominance amid U.S.-China rivalry, since failure to enforce these controls could enable Beijing to accelerate AI-driven military capabilities and erode global security.

National Security Imperatives

Without any AI export controls, China could quickly gain a military advantage by, for example, accelerating the deployment of drone swarms or significantly improving its cyber warfare effectiveness. Export controls on advanced tools like EUV lithography have severely hampered China's production, making it a marginal player reliant on smuggling and imports. Huawei is projected to produce only 200,000 AI chips in 2025, versus the millions of chips China imported.

Bans on Nvidia's H100 and A100 chips[3] have forced China to rely on less efficient domestic alternatives, raising costs and timelines, impeding their ability to deploy AI for military purposes. These controls have curbed but not prevented advances. A recent report from July 2025 notes that Beijing's top AI models face inference struggles due to chip shortages. Despite the controls, Chinese firms have still developed competitive AI models rivaling U.S. ones on benchmarks, though deployment at scale is limited by hardware shortages.

The Trump administration's July 2025 America's AI Action Plan reinforces this, prioritizing "creative" enforcement like embedding GPS trackers in AI chip shipments to detect diversions to restricted destinations, while assessing that Huawei had developed its Ascend chips using U.S. software or technology in violation of U.S. controls and their use as violating U.S. controls if used in sanctioned entities.

The Plan outlines 103 recommendations, from accelerating innovation to denying adversaries advanced AI access. China's August 2025 AI blueprint pushes for international engagement and global governance; however, some critics warn that easing controls now will eat into America’s advantage, handing China a strategic win. China’s October rare earth controls highlight this, leveraging their ability to counter U.S. chip bans, potentially delaying U.S. AI hardware production by years.

However, enforcement is not without its challenges, as demonstrated by the persistent smuggling despite the use of trackers. Additionally, dual-use ambiguities blur the lines between civilian and military AI uses. The May 2025 rescission pivots toward country-specific deals, but critics argue it weakens deterrence. Geopolitically, tighter controls risk U.S.-China escalation, while lax ones exacerbate inequities in global AI access by allowing the United States and China to capture the majority of economic and technological benefits, marginalizing developing nations. Ethically, how do we ensure controls do not hinder humanitarian AI uses like climate modeling or health diagnostics in underserved areas?

Geopolitically, tighter controls risk escalation, while lax ones widen AI access inequities, marginalizing developing nations. Ethically, controls must not impede humanitarian AI, like disaster prediction or health diagnostics in underserved regions.

The Case for Open AI and Innovation

Even as strict export controls enhance national security and slow adversaries’ adoption, they also harm U.S. sales and spur Chinese self-reliance. An open AI ecosystem drives exponential progress by enabling global collaboration, slashing R&D costs, and enabling applications in healthcare, climate modeling, and beyond. Experts estimate that existing controls have boosted domestic innovation while curbing China's GPU access by 20-30% and have had a "commanding" effect on the AI competition. However, blanket export controls risk isolating U.S. firms from massive global markets—China remains the world's largest AI consumer.

Recent Anthropic[4] updates tightened sales restrictions to Chinese-affiliated entities due to security risks, potentially forgoing hundreds of millions in revenue and limiting shared innovation. However, the Nvidia/AMD deal exemplifies how selective openness can fund U.S. infrastructure while accessing allied markets. Furthermore, some analysts forecast that overly restrictive policies could erode U.S. leadership, as China accelerates domestic chip innovation in response. Relaxed trade-linked exports could enable joint R&D, countering isolation.

China reacted in July 2025 in an effort to gain a foothold in the global market, as Huawei targeted the Middle East and Southeast Asia, with its older but still capable chips. October's rare earth controls signal further entrenchment, potentially fracturing global supply chains and forcing changes to higher cost alternatives.

Policy Recommendations

Implement export control recommendations from the AI Action Plan, prioritizing risk-based approaches. Since some adversary countries closely integrate civil-military activities, making end-user screening less effective, geographic-based controls should be used. In conjunction with these actions, develop metrics to measure their success.

Update the Wassenaar Arrangement for AI-specific clauses and coordinate with allies on tracking tech to strengthen alliances.

Offset market losses and incentivize innovation by offering subsidies for U.S. R&D and public-private collaboration.

Conclusion

The U.S.-China AI competition, amplified by the August 2025 chip deal, smuggling arrests, and October's rare earth escalations, highlights the need for a balanced approach: robust security without innovation chokeholds. Policymakers must embrace targeted strategies and multilateralism to secure leadership. Easing export controls now is premature, but rigid enforcement may be no better. The U.S. should strive for an AI future that's innovative, secure, and inclusive.

[1] Deep Seek is a Chinese artificial intelligence (AI) company that develops large language models.

[2] The Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies, a multilateral export control regime governing the international transfer of conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies.

[3] High performance Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) designed for AI datacenters.

[4] Anthropic is an American artificial intelligence (AI) startup company.